by Michael Crichton?”

.

His profile has understandably diminished since his death in November 2008 as a result of lymphatic cancer. However, he’s back in the headlines this week with the return to the US airwaves of ER star Noah Wyle, reprising the familiar part of a conscientious doctor at a busy hospital in a large American city.

But The Pitt isn’t a spinoff of ER, and it is a complete coincidence that it features Wyle portraying a character not unlike his ER character, John Carter MD. That’s according to producer Warner Bros – which has been slapped with a lawsuit by the author’s widow, Sherri.

She claims Warner Bros had entered talks with her for a new series set in the universe of ER, which Crichton had created in 1993 – drawing on his experiences as a student doctor in a busy emergency room. She alleges the studio then told her the project, which was to star Wyle, was “dead” – only for executives to hatch plans within the next 72 hours for an entirely different hospital drama, which just so happened to star Wyle, an executive producer on The Pitt. The huge, thumping difference being that The Pitt would take place in Pittsburgh rather than ER’s setting of Chicago.

“This case is not about whether someone can produce a medical drama, or even a medical drama starring Noah Wyle,” Sherri told Deadline.

“We would not have filed a lawsuit over that. This case is about whether Warner Bros. [executive producers] John Wells, Scott Gemmill, and Noah Wyle can develop and negotiate with the estate for nearly a year to do an ER reboot and, when they don’t get their way, pass off the same show under a different name as something completely new and original.”

The courts will decide whether her case has merit. As to whether The Pitt stands up as television… well, early word is that it’s passable but nowhere as addictive as ER, which made a star of George Clooney as dashing Doctor Doug Ross.

“There is an overwhelming déjà vu about it all, the elephant in the trauma room,” said the New York Times in a review which highlighted the ER-ness of the whole thing. “It certainly seems to want to be ER but that’s no great vice; shouldn’t everybody want to be ER? But it has fewer ideas, fewer moves, less energy, less specialness.”

and the 1978 period heist feature, The First Great Train Robbery, during which he struck up a life-long friendship with its lead, Sean Connery – who later helped Crichton cope with his frequent battles with depression.

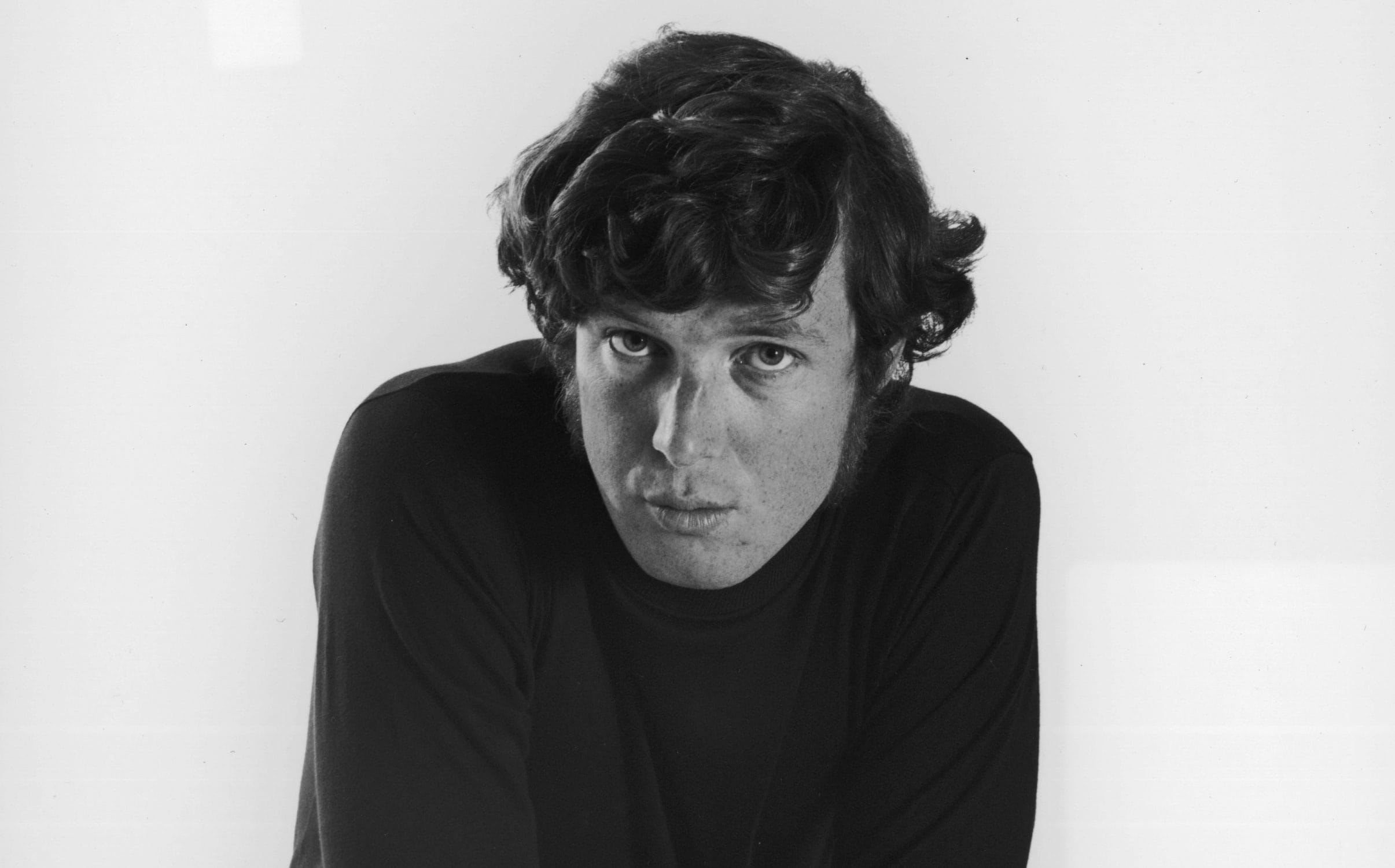

“Michael was always referred to as a Renaissance man,” George Clooney said to Vanity Fair. “That’s because he was so good at so many things. Doctor. Writer. Director. And he was a stunning six-foot-nine figure. He would walk in the room and all the rest of us mortals felt somewhat inadequate. It was something you had to see. He could reduce giant stars and brilliant directors to little kids looking up to this gentle giant.”

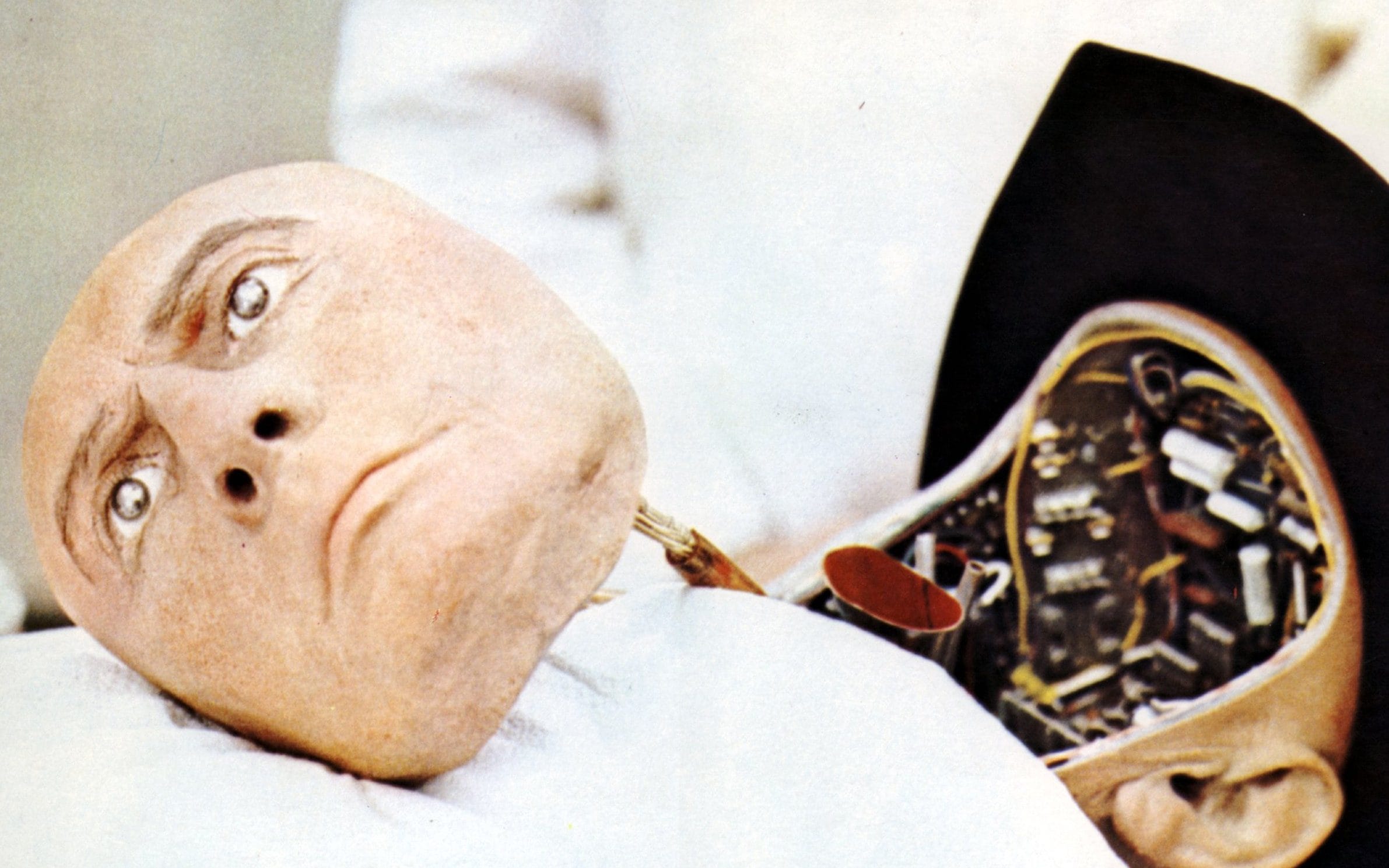

Even when he wasn’t behind the cameras, Hollywood couldn’t get enough of his work. The 1971 Robert Wise adaptation of his early novel, The Andromeda Strain, about a deadly virus from outer space, was a huge hit (Crichton wrote it while studying medicine at Harvard).

Then came Jurassic Park – based on his 1990 page-turner about dinosaurs resurrected using ancient DNA and featuring uncredited script work by Crichton. The 1993 dino romp was one of the biggest hits of Steven Spielberg’s career.

with his fourth wife, Anne-Marie Martin (a sequel, Twisters, blew the shutters off the box office last year).

“Crichton’s special attention to scientifically concerned heroes, his craftsmanship in designing very believable science fiction, and his ambitious approach to pursuing industry connections, all contributed greatly to his success at having his stories adapted to film,” says Ryan Rogers, producer and presenter of the Jurassic Park Cast, a podcast devoted to Jurassic Park and its sequel, The Lost World.

“What set Crichton apart, though, was that his heroes weren’t the every man, but scientists and doctors deeply interested in a field of study, commonly cautioning against the eager capitalist’s stubborn march towards ‘progress’. This added fictitious credibility to his works and, I think, made the world believe that cloning dinosaurs wasn’t so far-fetched. And in this way, inspired the world through his stories at what wonder we might be able to achieve, but also worry at what risks we’d be willing to pursue them.”

As is often the case with successful people, Crichton cut a contradictory figure. Jurassic Park is a love letter to dinosaurs, but the novel’s message is that scientific hubris can lead to a bad place. In the end, the dinosaurs break loose and eat everyone. As Jeff Goldblum’s Dr Ian Malcolm (a gangling odd-ball generally taken to be a stand-in for Crichton) tells Richard Attenborough’s John Hammond in the Spielberg film, “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should”.

“Michael Crichton’s immense popularity sparked a wave of imitators, filling bookstore shelves with works attempting to replicate his style,’ says the author (and Crichton fan) Spencer Baum.

“As a result, he’s often unfairly grouped into the broader category of ‘techno-thrillers’ that followed in his wake. This oversimplification overlooks his groundbreaking contributions to 20th-century fiction. Before The Andromeda Strain, and especially before Jurassic Park, sci-fi novels rarely featured such tightly wound, suspense-driven plots. Today, the style Crichton pioneered has become the norm. Readers, movie-goers, and TV watchers expect a dense, suspenseful plot where tech and sci-fi elements are grounded in realism.”

He could be tricky to deal with. At Harvard, he initially studied English but became fed up with what he regarded as the poor standard of lecturing. Frustrated, he submitted an essay by George Orwell under his own name – and received a mediocre grading. At which point, he decided to study medicine instead. “Now Orwell was a wonderful writer, and if a B-minus was all he could get, I thought I’d better drop English as my major.”

In Hollywood, he railed against the idiocy of studio executives whom he labelled “stupid’ after a 1994 adaptation of his novel Rising Sun made substantial changes to the plot. Married five times, he blamed the depression that would hit him “like weather” for his inability to maintain personal relationships. Among his many quirks was his insistence on eating the same meal every day when writing his novels. (He also claimed to not be able to start writing without some dirty laundry scattered about; in a 2003 interview, he said “a pair of Nikes” would serve at a pinch.)

Crichton wasn’t much bothered about what, at the time, was called “political correctness”. Today, he would surely risk cancellation. Rising Sun – later made into that Sean Connery/Wesley Snipes thriller he so hated – warned that corporate America was at risk of being colonised by Japanese business. Asked by the LA Times if he considered the Japanese inherently racist, he didn’t mince his words. “We’re talking about a historically inward-looking nation, an island nation, largely monoracial. That’s a good structure in which to have the rise of feelings of superiority about your own people as opposed to other people in the world.”

Express those opinions today and social media would bay for blood. He would also surely find himself in the firing line over the sexual politics of Disclosure, which argued that workplace harassment isn’t black and white and that it takes two to tango.

In the book and movie, Michael Douglas’s character is propositioned by his boss (Demi Moore). He rejects her – but only after things get steamy. Crichton’s big idea was that people who claim they are victims of sexual harassment aren’t necessarily painting a truthful picture – a point of view that, in a post-MeToo era, would see him figuratively burned at stake. “Why doesn’t he say, ‘I’m sorry? I gotta go now?’” he wondered, suggesting that Douglas’s character had played along with Moore’s sultry villainess. “We all know how to do that.”

In the end, Crichton was cancelled after a fashion. In his 2004 novel States of Fear, deranged environmental activists exaggerate the threat of climate change – only to be unmasked by a brave scientist.

Crichton had already played down a connection between greenhouse gases and rising global temperatures in a 2003 speech to the California Institute of Technology, Aliens Cause Global Warming (the title was satire: he didn’t believe climate change was all that big of an issue). For this, he was widely criticised: his friend, producer and director, Paul Lazarus, recalled to Vanity Fair how he had told Crichton, “Michael, you’re on the wrong side of history on this one”.

He was, however, defended by another colleague, Steven Spielberg, who said the author wanted to spark a debate about the environment. “People were not talking about global warming [when the book was published]”, he said. “And I think Michael was trying to shake things up and get people to listen, and I think he had to go out on a limb to get people to pay attention.”

Today, that controversy is largely forgotten. Nor is Crichton much of a household name – you won’t see him name-checked by New Yorker cartoonists. But his legacy lives on – in Jurassic Park and its many sequels. And in the still hugely popular ER (you can stream it on Channel 4). Seventeen years gone, he remains king of the smart techno-thriller, the dino resurrection drama – and the quick-paced hospital caper.

The Pitt may or may not be an ER clone. But for his widow’s claims of plagiarism to be even taken seriously in the first place is a testament to Crichton’s remarkable creative powers and to a legacy that goes far beyond peckish dinosaurs running amok on a primordial Disneyland.

Post a Comment

0Comments