Some people can listen to a piece of music and immediately identify the chords, pick out the intricacies of the bassline, recite the relevant musical theory, perhaps remember the drummer’s name.

they saw from that chef 20 years ago.

“That’s not something that anyone taught me,” Jones tells me. “That’s not something that came from anywhere apart from, I guess, my own brain and my own desire to recreate what I was eating.”

and let her prepare the family dinner.

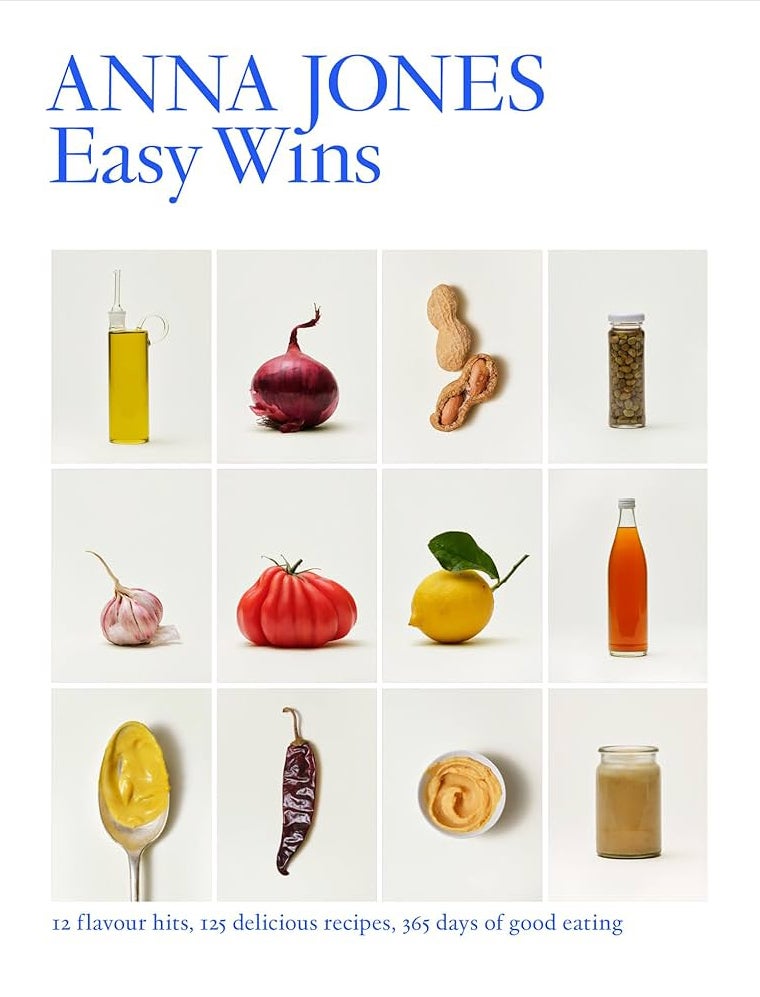

. Released in March, it sees her take 12 hero ingredients that she says are guaranteed to make recipes like double lemon pilaf, traybake lemon dhal and miso rarebit not only taste amazing, but come together in no time at all for those nights when you want maximum flavour with minimum effort.

This life in food almost never happened, though. The next part of the story is a tale as old as time for chefs: where Jones studied economics and philosophy at university, with a view to work in policy around third-world debt, which she quickly tired of before returning to her passion for cooking. Some of the biggest names in food started out as accountants, architects and other such desk-bound careers. A lightbulb moment was reading an article on “how to find your calling”. “It said you can determine your real passion by the Sunday supplement papers you turn to first. It was like a little lightbulb went off. I was like, ‘Yes! It’s always been cooking!’”

column, that’s a lot of inspired people.

’s 2004 televised apprenticeship to get unemployed young people into the hospitality industry, which saw her go on to work in his wider business for seven years. Whatever you think of the Naked Chef, Jones considers herself lucky to have been a part of it. “I mean, it was just brilliant,” she says. “I got the benefit of it being when Jamie was just starting out and rightfully everyone was very excited about working with him. It was an education in food that even if I’d had the money for… well, it was a money-can’t-buy-experience, really.” They’re still in touch; he’s just a phone call away for advice and is a big supporter of her projects. “Jamie’s always been very supportive of me and has always been a great cheerleader for my work, which I’m really, really grateful for. He’s done some amazing work and I think he deserves a lot of credit.”

era. One of (mostly male) chefs with fiery tempers, aggressive behaviour and profuse language. While she says Oliver’s kitchen was a nurturing one, it did paint a picture of a future she wasn’t sure she wanted.

“I understand the need for direct communication in service, because it’s a frenetic environment, there’s hot stuff around. In some ways, that very direct, slightly hierarchical communication is necessary during service,” she says, always the diplomat, never naming names, though she must know them. “But I really don’t understand why outside of service that kind of hierarchy and some of those behaviour patterns need to exist. Luckily, I think things have changed.”

But she believes the kitchens of 20 years ago “were maybe not a particularly nurturing environment for a 20-year-old woman. Back then, I think if I’d just strolled into a Michelin-starred kitchen, I wouldn’t have loved it.”

At any rate, she had already chosen family over career, which is not something you hear very often from a successful woman in a male-dominated industry. “I knew I wanted at some point to start a family and I couldn’t really see how working in a restaurant at that time and eventually having kids and a family would work.”

The harsh realities of being a parent, especially a mother, in the restaurant business has always been a hot topic. Working in professional kitchens is already a physically demanding job with little accommodations for pregnant women: few restaurant businesses offer maternity or paternity pay beyond what’s statutory, and it’s often not well paid enough to afford childcare. When she saw Oliver’s team writing recipes and staging photoshoots for his cookbooks, “it felt like a meeting point of all the things that I loved: writing, that creative, artistic sense of bringing the food to life in a photograph, and then, of course, the cooking and food.” She knew she wanted to write cookbooks, so that’s exactly what she did.

I knew I wanted at some point to start a family and I couldn’t really see how working in a restaurant at that time and eventually having kids and a family would work

Since then she’s become one of the standard bearers for modern British vegetarian cooking. She hasn’t eaten meat in 15 years. But her decision to give it up didn’t have anything to do with altruistic sensibilities, as you might expect. It wasn’t to do with animal welfare or the environment or health. It was, for want of a better word, to do with boredom. “I was cooking a lot, I was eating a lot, I was trying a lot. And I think I felt a little bit jaded.” She decided to stop eating meat and fish “to reset my palate, reset my excitement around food”. After just a few weeks, she realised she’d never been more excited about food than when she wasn’t eating meat. “The longer I slept on it, the more the concept of eating meat and fish became abstract to me. I’ve never gone back.”

, came out in 2014 not long after she’d turned vegetarian, and was as much a guidebook to making the switch for herself as it was for her readers. “It’s all about the staples that I reworked for myself when I stopped eating meat,” she says, plus a few ideas she had (or pinched, she jokes) while working with Oliver.

, published in 2017, that Jones started to come into her own. “I would say that’s my most foodie book,” she says. It’s a veritable tome of a cookbook – it could hold open a door – with over 250 recipes that lean heavily into Jones’ love for seasonal eating. “I think eating seasonally when you’re putting vegetables at the centre of your diet is even more important because we’re relying on the flavour of these amazing vegetables. I don’t need to tell you that an in-season strawberry tastes completely different to one flown in from somewhere else.”

– I’ve just spent the weekend putting up shelves for my hundreds of cookbooks, but this one takes pride of place, I tell her. Given that it was published in 2021 when all anyone wanted to talk about was the benefits of a meat-free diet, it’s not surprising that it’s her most sustainability-focused book. “I felt a bit of an urgent need to be more upfront about the importance of us putting vegetables at the centre of our diets, both for our health and because it tastes amazing, but also about the world around us.”

doesn’t seek to preach. “I know not everyone wants or can be vegan or vegetarian and I think most people aren’t going to read a book about sustainability, but they’re very happy to flick through a recipe book.”

is her fifth book and reflects where she is now, simultaneously raising an eight-year-old and a one-year-old. “I want to make really delicious food for my family, but I feel like time is short. So I wanted to reverse engineer those recipes where two and two add up to a hundred, where you’re doing a simple process with simple ingredients, but there’s that extra bit of recipe magic that turns it into something really, really delicious.”

That recipe magic is a capsule of 12 pantry ingredients, from tahini to lemons, olive oil to miso, that will elevate simple base ingredients, bouji-fy the boring. “For example, a teaspoon of miso added to some roasted vegetables and tossed together will really amp up the flavour of your food, but the effort is so minimal.”

Her life has certainly changed since her first book a decade ago, but so has the landscape of the food world. “In the 20 years I’ve been cooking, my job has changed beyond recognition. So has the vegetarian conversation,” she says. As a vegetarian back then, “there were so many things that you couldn’t get your hands on. I’d have to go around like 20 different shops to get all of the things that I needed.” Nowadays, everything is so immediately available.

addresses that challenge, in some ways, she sees it as a loss. “There’s absolutely no point in sharing the sort of cheffy recipes I might be able to cook because, you know, no one is going to make a bechamel sauce on a Tuesday night.”

If her books have kept a finger on the pulse of food for the past 10 years, what might be next, I wonder? “Looking ahead, I think it’s becoming ever more urgent for us to move away from factory farming and the foods that are damaging the world around us,” she muses. She says regenerative farming – a way of farming that works with nature to help tackle climate change and ecological collapse – is the next big buzzword, but it’s not yet accessible enough to be mainstream. For now, regenerative farmers are a minority, and their products usually prohibitively expensive. “I think that at the moment the regenerative conversation is essentially for people who either go out of their way to seek it out, or for people who can afford it. And so to be able to bring these kinds of climate-positive businesses and food to everyone, I think that’s an interesting space.”

Ever the optimist, Jones is always looking forward, and suggests we do, too. “When it comes to climate, I think guilt is not a useful emotion, I think looking back at what we haven’t done is not useful,” she says. Instead, she favours keeping calm and keeping it simple. “We make 40,000 decisions a day. A great number of those will be related to food, so every day is an opportunity to make some good decisions. Every day refreshes with new opportunities. I think that’s a really great way to look at it.”

‘Easy Wins’ is out now, published by Fourth Estate. Anna Jones appears at Hay Festival on Thursday 23 May at 5.30pm; hayfestival.com

.

Post a Comment

0Comments