sacked by his German employer for sticking to his vow of never flying won compensation in an unfair dismissal lawsuit, £63,000 of which he donated to environmental activism.

, leading to the termination of his employment.

.

The settlement brings to a close a case that has become emblematic of the tension between climate-conscious practices and workplace obligations. While the exact severance amount is confidential, Dr Grimalda has pledged €75,000 (£63,000) of the payout to climate protection and activism.

Initially, IfW had approved his plan to travel back to Germany by slow, low-carbon methods such as sea and land routes. However, after logistical delays caused by visa issues, security threats, and even volcanic activity, the institute demanded he return by plane. When he refused, citing his commitment to climate principles, his contract was terminated.

The legal dispute centred on whether Dr Grimalda’s dismissal was valid. While the Kiel Regional Labour Court initially ruled in favour of IfW in February 2024, an appeals process led to the recent settlement. The court acknowledged “incompatible ideological convictions” between the two parties but repealed the immediate termination, exonerating Dr Grimalda of any breach of contract.

I hope that my case will encourage more employees, institutions, and companies to actively support the transition from fossil fuel-based economies to decarbonised and people-centred societies.

“This case highlights the growing intersection between labour law and climate-conscious practices,” said Jörn A Broschat, Dr Grimalda’s attorney. “It represents a milestone in the emerging discussion about the rights of employees to stand up for their climate principles as part of their professional obligations.”

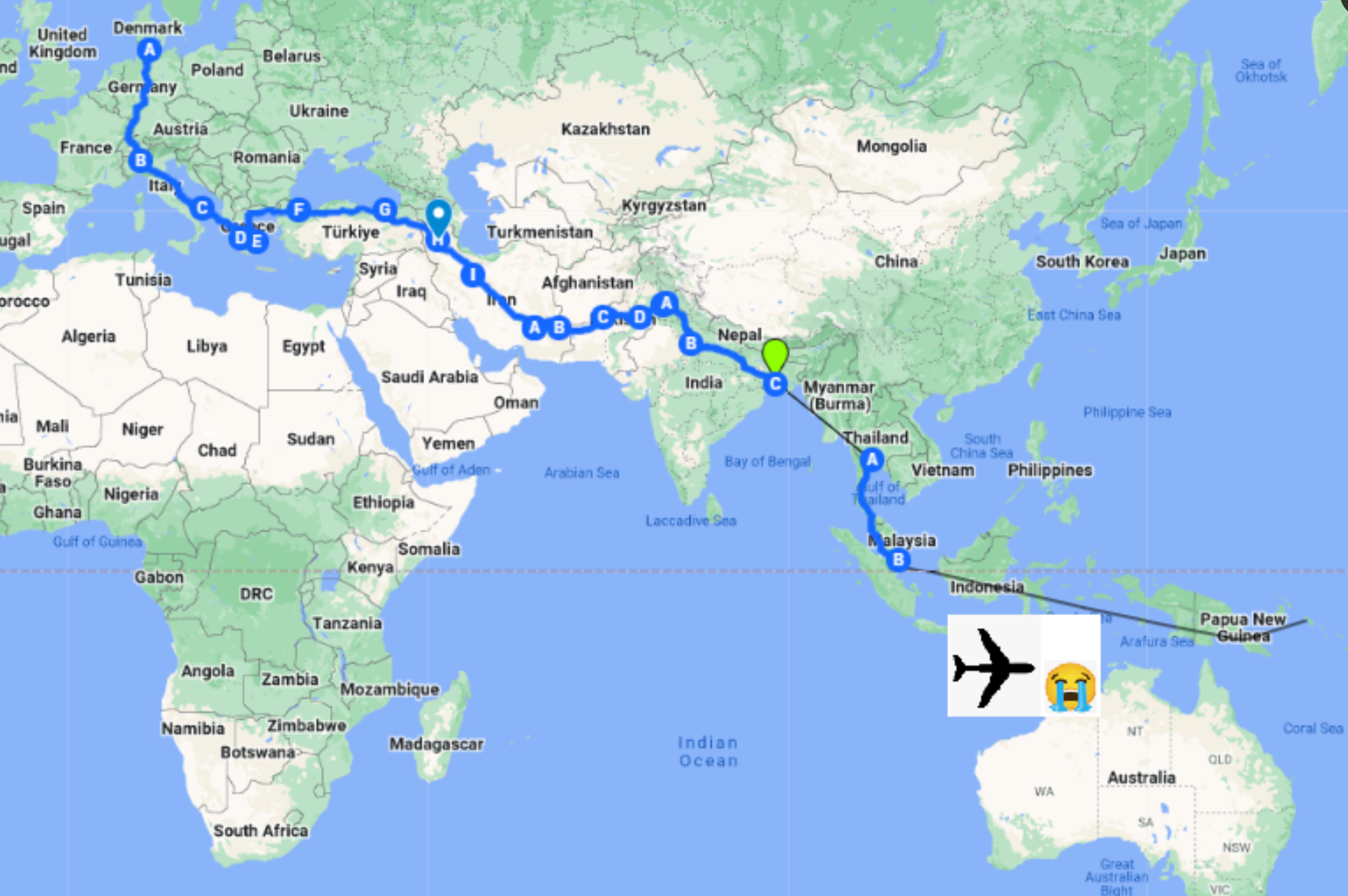

Dr Grimalda’s journey to Papua New Guinea, spanning 28,000km (17,000miles approx) by cargo ship, train, and ferries, cut his emissions by a factor of 10 compared to flying. On the outbound journey, he travelled 15,000km overland through Iran, India, and Thailand. His resolve to slow-travel strengthened during his fieldwork, where he witnessed the impact of climate crisis on vulnerable communities in Papua New Guinea.

last year. “Sea-level rise is not because of their emissions. People from the US and Europe, with the highest carbon footprints in the world, bear the greatest responsibility.”

He said that his slow travel plans emitted 400kg of carbon dioxide, compared to 4,000kg by flying, a figure equivalent to the average person’s yearly emissions in Papua New Guinea.

Reflecting on the outcome, Dr Grimalda expressed mixed emotions. “I feel sad and happy at the same time,” he said. “Sad because I lost a job I loved. Happy because the judge implicitly recognised the impossibility of dismissing an employee because of his refusal to take a plane.”

“I hope that my case will encourage more employees, institutions, and companies to actively support the transition from fossil fuel-based economies to decarbonised and people-centred societies,” he said.

While he says the job applications he made this year were unsuccessful, he is determined to carry on with his research.

“In 2025, I plan to slow-travel to Papua New Guinea again to further investigate the adaptation of the local population to climate change. Once I am back, my work as a climate activist will resume.”

As extreme weather events intensify worldwide, from Los Angeles to Papua New Guinea, Dr Grimalda’s case has sparked broader discussions on how labour laws should account for the climate crisis. “It’s time for lawmakers and collective bargaining parties to enshrine climate-conscious practices as labour rights,” said Mr Broschat.

“Academics have multiple channels to alert the world to the climate and biodiversity crisis, and modifying their personal greenhouse gas contributions is an important way to demonstrate credibility,” said Wolfgang Cramer, Research Director at CNRS and a former contributor to the IPCC report.

.

Post a Comment

0Comments